How the dramatic first South Atlantic aerial crossing influenced modern navigation

In 1922, to celebrate the centenary of the Independence of Brazil, Portuguese aviators Carlos Viegas Gago Coutinho and Artur de Sacadura Cabral set out from Lisbon with two goals: to make the first crossing of the South Atlantic and to test out a new astronomical navigation instrument. Landing in Rio de Janeiro on 17 June 1922, they achieved them both and their successful flight, during which they used no other means of navigational support, made a major impact upon the future of aviation.

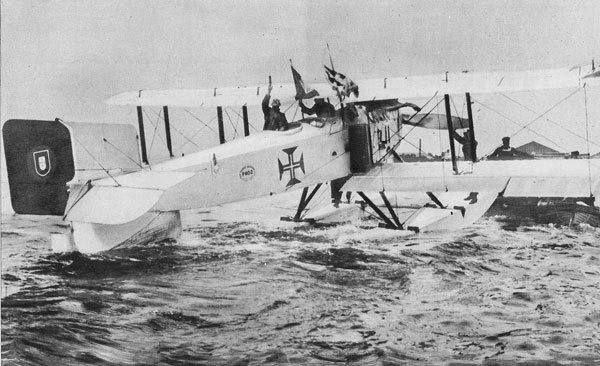

The duo's aircraft – a Fairey IIID, modified as the F.400 float plane – was fitted with a ‘precision sextant’, an instrument that could be used to measure the altitude of a star without the need for a visible horizon. Using two bubbles, similar to a spirit level, this new device had been invented by Gago Coutinho himself and was used alongside a path corrector which calculated the angle between the longitudinal axis of an airplane and the direction of flight, taking into account the intensity and the direction of the winds.

Image from facebook.com/Lusitania2022

A new era of aerial navigation

Two previous transatlantic crossings, both made in 1919, had been achieved using radio communication (‘Directional TSF’). Albert C. Read headed a team of four flying boats from New York to Newfoundland and across to the Azores, Portugal, with one completing the journey to land in Lisbon. They were aided by a fleet of 60 US Navy warships to help guide the aviators. Just two weeks after this, British duo Alcock and Brown, also using Directional TSF, crossed from Newfoundland to Ireland in a Vickers Vimy biplane.

The day before Read’s arrival in Lisbon, naval officer and topographer Sacadura Cabral submitted a proposal to cross to progress Portuguese aviation and strengthen the ties between Portugal and Brazil. The request was granted, and Sacadura Cabral’s good friend, the cartographer, historian and aviator Gago Coutinho was selected to navigate the crossing.

The duo believed that marine navigation could be adapted for aviation purposes, and following their research and development, an initial test of the navigational equipment was made, with the pair successfully flying from Lisbon to Funchal, Madeira, in March 1921, using the new instruments. The route was to be a perfect straight line, with ships in three locations to verify the calculations. The journey took 7h and 30 minutes.

Destination: Rio de Janeiro

Following their success in 1921, preparations for the South Atlantic crossing started in earnest. The naval ship ‘República’ was to provide refuelling services, along with two other boats for support. The planned stops were: Las Palmas, S. Vicente (Cape Verde), Praia (Cape Verde), St. Peter (& St. Paul’s) Rocks, Fernando Noronha, Recife, Salvador da Bahia, Porto Seguro and Vitoria before arriving in Rio de Janeiro.

The ground-breaking voyage began at 07:00 on 30 March, with the Fairey III ‘Lusitânia’ taking off from Lisbon, but just like many early aviation adventures, the flight was not destined to go according to plan…

Despite the adaptions made to the aircraft to compensate for the excess load, the weight was to affect the sea take offs and landings, with mechanical adaptations needing to be made en route. Then, during the longest stretch to St Peter’s and St Paul’s Rocks, fuel was a concern for the Lusitânia. Luckily for the airmen, they had just enough fuel to reach the destination but one of the floaters was taken out upon landing in the sea, causing the plane to fill with sea water. The aviators were rescued but the aircraft was not so fortunate.

Yet such was the support for the courageous crossing attempt, that the Portuguese government was willing to send a replacement Fairey 17 – named ‘Pàtria’. Due to weather constraints, the aircraft was not able to be delivered directly to the pair who were waiting at St Peter’s and St Paul’s Rocks, but in the interests of staying true to their mission, the duo collected it from Fernando Noronha, planning to fly back to St Peter’s and St Paul’s Rocks in order to begin the next stretch.

Sadly, this aircraft was destined to go the same way as the first hydroplane. Facing heavy rain and fuel carburation hiccups, an emergency landing on the sea was accomplished, but the engine did not restart, and so a second Fairey IIID slowly sank into the dark waters after the pilots had been rescued by the British freighter ‘Paris City’.

A third Fairey was supplied – named Santa Cruz by the Brazilian President’s wife – and had more luck. The two aviators made stops as planned in Recife, Salvador de Baia, Porto Seguro and Vitoria, finally arriving in Rio de Janeiro on 17 June 1922 to a warm welcome, not only for their success in making a historic first flight across the South Atlantic, but also for the beginnings of a new era in ariel navigation.

Despite a duration of 79 days for the mission, the actual flight time was just 62 hours and 26 minutes.

A lasting legacy

The Portuguese duo were honoured by their government for their achievement and contribution, receiving numerous awards and medals and in 1922, both were recognised by the Portuguese Navy: Gago Coutinho was promoted to Vice Admiral, his partner promoted to Commander with distinction. Sacadura Cabral had further ambitions: he began plotting another voyage – a circumnavigation. A huge challenge, diplomatically, financially and practically, the planning stages took some time, and it was whilst bringing a publicly financed Fokker 4146 from Amsterdam to Lisbon for the attempt, that Sacadura Cabral disappeared alongside his co-pilot, José Correia, in foggy weather over the English Channel. The wreckage of the aeroplane was recovered on November 18 1924 but their remains were never retrieved.

After the loss of his friend, Gago Coutinho dedicated himself to history and research in aviation and navigation, sharing his thoughts and findings through papers, lectures and publications, also writing two volumes of work about Nautical Discoveries in the early 1950s. He became an Admiral in 1958, and passed away not long afterwards, one day after his 90th birthday on 18 February 1959.

A monument of the Fairey III to mark the brave aviators’ achievements was erected at the Belém Tower in Lisbon, and the surviving aircraft is on display at Lisbon’s Maritime Museum.

Image from facebook.com/Lusitania2022

The Precision Sextant was later adapted to permit navigation during night flights, with an internal illumination system. Fellow Portuguese airmen Sarmento Beires, Jorge Castilho, Duvalle Portugal and Manuel Gouveia continued to drive the national agenda for pioneering aviation and colonial relations, using the adapted instrument to make the First Aerial South Atlantic Night Crossing in 1927. From this date onwards, pilots were easily able to fly for long distances away from land, and at any time of day in all light conditions.